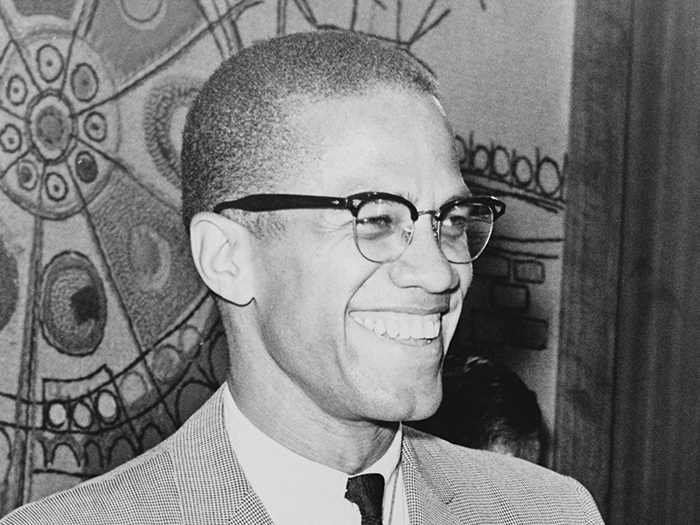

Born on May 19, 1925, Malcolm X remains one of the most transformative figures in modern history – a man whose journey from adversity to activism continues to inspire generations. As we commemorate his 100th birthday today, we reflect on his indelible legacy as a human rights champion, revolutionary thinker, and proud Muslim.

Early Roots: Seeking Truth

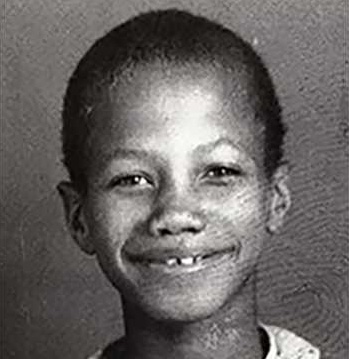

Born Malcolm Little, his early years were shaped by a family deeply rooted in the struggle for racial equality. His father, Earl, a Baptist preacher, instilled in him stories of liberation like Moses leading the enslaved to freedom. His Grenada-born mother, Louise, wrote for Garvey’s Negro World newspaper and shared Garvey’s philosophy and teachings of black empowerment with Malcolm and his siblings.

After his father was killed in a suspicious 1931 streetcar accident (widely believed to be a lynching), his mother, Louise, battled poverty and racist authorities who deemed her “unfit” for resisting forced sterilization. By 13, Malcolm watched his family being split by foster care—a trauma which fueled his later rebellion as “Detroit Red” before prison transformed him. It was during his time in prison, however, that Malcolm encountered the teachings of the Nation of Islam—a discovery that initiated a spiritual awakening.

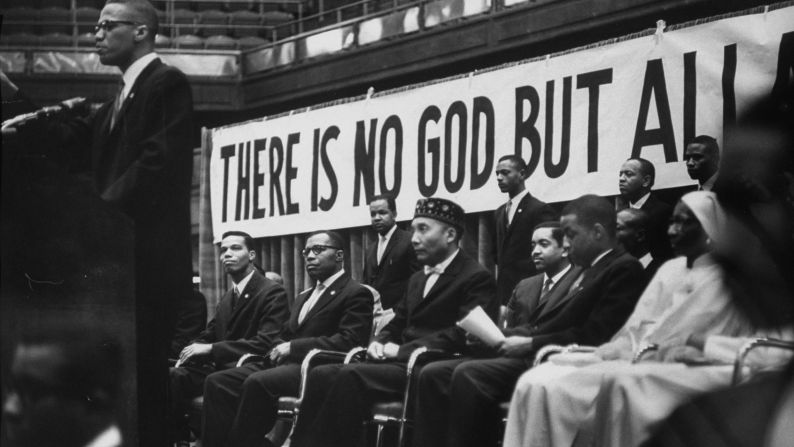

Nation of Islam: Discipline & Community

By the late 1940s, Malcolm had joined the Nation of Islam (NOI), adopting the name Malcolm X and championing self-reliance for black people. As an NOI leader, he established over 30 temples, emphasizing that faith required tangible action: “Prayer alone won’t end racism,” he often declared. His teachings combined strict moral codes—rejecting drugs and alcohol—with a call for economic independence through Black-owned businesses. Critical of mainstream civil rights leaders, he argued passionately that freedom was not a gift to be granted but a right to be seized.

The Turning Point: Pilgrimage to Mecca

A pivotal shift came in 1964 during Malcolm’s pilgrimage to Mecca. There, he witnessed Muslims of all races praying side by side, an experience that shattered his earlier views on racial separation. “I’d never witnessed such true brotherhood,” he wrote, describing the unity he saw as transformative. This journey led him to embrace mainstream Islam’s universal ideals, and he adopted the name El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, symbolizing his renewed commitment to equality across all boundaries.

Final Year: Building Bridges

In his final year, Malcolm underwent a profound metamorphosis across three dimensions, emerging as one of America’s most radical yet spiritually grounded thinkers. His Hajj pilgrimage shattered his Nation of Islam worldview. Praying alongside white-skinned Muslims in Mecca, he said: “I’ve eaten from the same plate, drunk from the same glass, slept on the same rug—while praying to the same God with fellow Muslims whose eyes were bluest blue, hair blondest blond.” This birthed his Universal Islam philosophy—a faith transcending race, embodied in his new name El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz. He established the Muslim Mosque, Inc., blending orthodox Sunni practices with Black liberation theology.

Let’s Keep His Legacy Alive

Malcolm’s journey reveals how faith can evolve into a force for collective healing, advocacy, liberation, and justice. On this centennial, his life reminds us that we too can and must evolve and continue to fight for freedom for ourselves, each other, and the global family.

Malcolm X as a Husband and Father: A Legacy of Love and Resilience

Behind Malcolm X’s towering public persona as a revolutionary leader lay a deeply devoted family man. His marriage to Dr. Betty Shabazz in 1958 was not only a union of hearts but a partnership forged in shared purpose. Betty, a nurse and educator, became Malcolm’s anchor, providing emotional stability amid the turbulence of his activism. Their relationship, rooted in mutual respect and ideological alignment, thrived despite relentless external pressures — FBI surveillance, death threats, and Malcolm’s grueling travel schedule. Letters exchanged during his frequent absences reveal a tender intimacy, with Malcolm addressing Betty as “My Dear Wife” and expressing longing to hold their growing family. Together, they raised six daughters — Attallah, Qubilah, Ilyasah, Gamilah, Malikah, and Malaak — in a home filled with political discourse, Islamic teachings, and deliberate lessons on Black pride.

As a father, Malcolm defied stereotypes of the absent revolutionary. He prioritized moments of normalcy, playing with his children on the living room floor and teaching them to recite Arabic phrases. Yet his parenting was intentional: he instilled in his daughters an unshakable sense of identity, once writing, “You must never be misled by [the world’s] rejection… You are African.” His assassination in 1965, witnessed by Betty and their four eldest children (then aged 6, 4, 2, and 6 months), cast a long shadow. Betty, suddenly a single mother, shielded her daughters from exploitation while ensuring Malcolm’s legacy lived through them. The Shabazz sisters would later become educators, activists, and custodians of their father’s intellectual heritage — a testament to the foundation of love, discipline, and social consciousness their parents built.