THE DATA

We had several immigrant teachers who treated the mostly Black student population like we were “stupid” and backwards/limited in our understanding of Islam and ability to be true Muslims. There was a distinct air of superiority in their attitudes towards the Black students. —Fatimah

I was treated poorly by both teachers and students despite my father being a teacher at the school. I was bullied severely by students for being Black, homeschooled, and a niqabi and no one ever truly made me feel welcome. I was called names, cornered, made fun of, and was never included with the other girls’ activities. It’s an experience that lives with me to this day. —Aisha

The Arabs were at the top of the hierarchy and the Blacks were at the bottom. And that hierarchy was perpetrated. —Noor

This article explores the central question of my thesis: the question of antiblackness in Islamic schools in the US. After conducting the three forms of data collection, I collated the data from the survey, focus groups, and interviews. I went over the data to gather themes, five stood out because they reoccurred across the data.

These five core issues were:

- Name-calling

- Disparagement

- Curriculum

- Unfair discipline and lack of transparent policies

- Lack of respect for students’ identity, culture, and history

1. Name-Calling

When alumni were asked if the students around them used the n-word, the word ‘abid, or some derogatory term, 43 survey participants (67.2% of the sample) said yes. When we exclude the schools attended by participants who expressed high levels of belonging, happiness, and connection[1] the number jumps to a staggering 76.7%.

Two survey respondents mentioned that the use of the n-word was a daily occurrence and focus group B said the use of ‘abid was very common.

During my interview with Farzana, a co-founder of a K-8 institution on the East Coast, she shared with me an incident around name-calling. A sixth grader informed his teacher that somebody called him the n-word. But he said, “But you know, it’s okay, I don’t really mind, you know, I’m used to it. He’s my friend, it doesn’t matter.” Her school was very intentional about belonging, respect, and character, so this incident was unexpected. The student, Muhammad, is Somali. The administration of the school pursued the matter even though the student claimed that it was okay. The administrator made sure that she communicated the importance of his voice and his experience and that what was said was wrong and unacceptable. They also spoke to the boy who made the disparaging remark and his parents. This school uses restorative justice, and they used that approach with this incident. No survey participant had the school deal directly with incidents of name-calling when students shared this with teachers.

Idris, a twenty-five-year-old alumni of a Midwestern Islamic school, said, “All throughout freshman and senior year, you would have people saying the n-word, dropping the n-word like casually. They thought that was the funniest thing in the world. Um, and yeah, these things are far from uncommon.” In the beginning, Idris shared the outrageous use of the n-word with his parents. They told him to speak to his teachers but because of the teachers’ implicit and explicit acceptance of other antiblack behavior, Idris’s response was “That’s realistically not gonna do anything.” He stopped speaking to his parents about the problems in school. “I’m not gonna be the tattletale kid. I’ll just handle it myself.” Subsequently, Idris gained a reputation for getting into arguments.

Idris also shared that a student compared him to a Black disabled character in a book they were reading in class. The teacher’s response was “Guys, you have to stop arguing.” I’m like, “I’m not arguing. She’s, she’s arguing. She’s being legitimately racist.” Idris continued, “It’s constant at an Islamic school[2] and teachers don’t really do all that much in these instances.”

2. Disparagement

“I was often made fun of for being Black or being the child of converts,” Nsenga said in the comments box of the quantitative study survey. Her experience was not unique. The survey did not have a question about disparagement, but students spoke about this under the questions on “happiness,” “feeling that they mattered,” “respect for culture,” “derogatory language,” and “was your Islam seen as valid.”

Yes. They saw me as a Muslim. But they also saw me as beneath them. A slave: ‘abid.

I had a friend in high school who was a Palestinian and his father owned a series of corner stores and liquor shops in predominantly Black neighborhoods. “We know that they steal. So, we don’t want to ever leave them not being watched.” “No, not you, Idris, we know you’re different.” —Idris

Idris mentioned that he grew up in a lower-middle-class white neighborhood that had a chapter of the Klan. He felt that his Arab and Desi classmates learned this disparaging attitude from “racist white people.” What shocked him was that the members of the immigrant community articulating these myths “had just come to the country like recently.” This baffled him because he had come to this school with an idea of Muslim solidarity (ummah) but was left jaded.

3. Curriculum

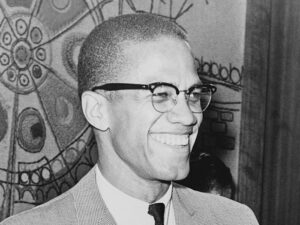

“It’s either Bilal or Malcolm X and the way Malcolm X is portrayed was violent.”

Shahidah, a thirty-one-year-old alumni of an Islamic school, expressed her hesitance to embrace one of the two curriculum figures representing Black Muslims because of the way she was taught. I saw evidence of this kind of thinking in a training; an Islamic school teacher stated that “MLK was a kind Christian and Malcolm an angry Muslim.” For Shahidah, embracing Malcolm was equivalent to embracing violence. She was conflicted because she wanted to embrace an important figure, but the parameters she was given made it hard for her.

Shahidah continues, “Yes, Bilal, Bilal, Bilal, and it’s always, ‘he called the adhan, he has done so much, he’s seen so much, he’s was with the Prophet for so long, like, there’s more to him than that, you know.”

Salma added, “They always mention he’s a slave, and he called the adhan.” This, for Salma, reinforced the idea that Black people are just slaves. Shahidah adds, “It’s Blacks who arrived in this country as slaves.” She resented how her history was told excluding the story before her ancestors arrived in the Americas, erasing stories of “being warriors, being kings and queens, and commanders of armies. That stuff is just really frustrating!” Bilal was a close companion, one of the earliest adults to accept the teachings of Prophet Muhammad. In the survey, my respondents noted that the extent of seeing themselves in the curriculum was a very cursory mention of two iconic figures without the rich context that helps inform learners so they can really benefit from the mention of these individuals. In the survey, one participant said, “Black history was a very quickly touched upon topic. Teachers would go over a day’s worth of material and that would be it. Nothing was really discussed.” The story of Bilal was only told when trying to discourage accusations of racism. Nailah said that Bilal and Abraha are the only examples that come to mind. Hawwa said, “I lived the Black American history story.” For her living and being educated in a BMBL space gave her a strong sense of self as a Black Muslim. Salaam remembers just basic teachings like who Bilal was.

For Imad, the African American experience and the African foundations of Islam in America are often overlooked. He sees this lack of awareness in Islamic schools and mosques that aren’t predominantly Black. He is a teacher in a private school whose focus is on belonging. He shared that incorporating the study of the following areas in the school curriculum can reflect Black Muslim history and an appreciation and respect for Blackness:

- Africa has been integral to Islam from the beginning

- African kingdoms

- Scholars who were enslaved and brought to this stolen land

- African American freedom struggle that opened up immigration to many Muslims today

- African American leaders historically aligning themselves with the Palestinian struggle

Finding commonality in curriculum leads to solidarity. This solidarity can be in terms of Palestine or shared experiences of oppression. It would be powerful to see curricula that show Islam as a force that is anti-oppression and as a framework for addressing exploitation and oppression in the world. This can help students see the commonality and importance of caring about oppression in its various forms.

I am a teacher now and I would love to work in an Islamic school but when I never saw myself in the curriculum or in the teaching body it is hard to see that as a possibility. —Idris

Idris shared that incorporating Black history into the school curriculum would have helped. His observation was that his Islamic school made something of an attempt with Malcolm X. His complaint though was that in Black history, the school only taught what overlapped with Islam. They said, “We don’t do American history or any other history.” Malcolm X’s impact on the US did not fall within the purview of what was covered. Idris felt that the story of the Black Panthers should be taught and that students should learn about Fred Hampton, Kwame Toure, and the freedom movement of MLK. “Yet they teach this one narrow section of Malcolm’s life every single year. The kids are sitting there like, you know, glazy-eyed, not paying attention, just enjoying time out of class. And that’s kind of the extent of Black history.” Idris is very interested in African history and wanted to learn about West Africa, but this was not covered in his four years at an Islamic school. “Anything I know came from learning about it (myself) through research.” He proceeded to share that he had heard lots of racist, lazy stereotypes about West Africans. He had one Nigerian classmate and the guys would make comments about her around him. Idris would remind them that “we’re Black, I’m Black too.” They would respond, “No, no, but you’re different. You’re from—” to which Idris would interject “But I’m Black. What you’re saying about her you’re saying about me.” The students would find ways to show that Idris was different from his Nigerian classmate. Idris felt that had the curriculum[3] represented more than the occasional speech about Bilal or Malcolm, it could raise awareness and reduce stereotypes.

Idris shared his gratitude for having an AP History teacher who had them read Howard Zinn, which went into more depth about the stories of the oppressed.

Halimah spoke about how the curriculum reinforced the idea that Bilal is the only Black person around Prophet Muhammad. That is all they talk about! “We don’t talk about Um Ayman, we don’t talk about the woman who brought the prophet into this world.” Salma said, “Like we, we, we don’t, we don’t talk about that. And, if they would have talked to me about Um Ayman, Barakah, you know, uh, and Zaid, and Usamah, like these sahaba I would have loved being Black even more.”

The Importance of Critical History

One participant spoke about the importance of recognizing the different backgrounds that were being placed together and the importance of these students being taught history. Critical history is a term I am using to describe integrating critical thinking and Islamic studies into social studies. It involves giving students the space to learn about Black culture, what Islam says about culture, people’s differences, and how to reconcile the stereotypes we see the world through versus how we should see the world.

Like you have people who were, you know, immigrants from India and like were active participants in a caste system and may have been raised to have a certain view of people who were lower class inherently. And then you also have them in school with second-generation Black American Muslims whose parents may be lower middle class and poor. —Idris

Here, Idris shares his concerns about not teaching history and just expecting children from different backgrounds to just get along in a highly racialized society. How can they respect each other without any real guidance from the adults around them?

Similar to the friend I talked about whose father was a bit racist and ran the store in the Black community, we have to be very careful to make sure that the future generations of Muslims are being educated in a way that is not adding to the problem that we already see in this country, right? —Idris

Idris was shocked to hear rhetoric like “they’re illegals. I got here legally! They should all be rounded up and sent like animals across the border.”

4. Unfair Discipline and Lack of Transparent Policies

Over half of the survey respondents (54.7%) claimed they experienced injustice in school. In the focus group, women went into more depth about this injustice. They discussed the policing of their clothes and the disparity between their consequences and the consequences of other non-Black female students found doing the same thing.

Haniya shared, “In eighth grade when a girl and I ditched class I ended up getting suspended and she didn’t.” Shahidah shared, “I felt a sense of belonging in that we were all Muslims.” Her school was relatively diverse with Palestinians, Egyptians, African Americans, and other groups. But when it came to punishment, even for doing the exact same thing, she received harsher punishments. Shahidah then shared an incident where a group of her classmates decided to go to the park on the last day of school. All ten or so of them of them skipped school. The principal found them and wrote down their names. Shahidah had a financial reward withdrawn as a consequence. None of the other girls received any consequences. She shared that eventually it was resolved after she apologized, but she felt it was unfair that she was the only person held accountable out of the whole group. Shahidah described the hyperattention Black students faced when they would be forced to remove their earrings while that same demand would not be made of Arab students, even those wearing larger earrings than the African American students.

Oh yeah, I mean if there was something that went wrong, I was going to be the first accused of it. I remember the vice principal said she had a video of me hitting a student and starting a fight in the cafeteria. There was no camera, and I had never put my hands on anybody. She told me I would be suspended. And I knew for a fact that this was because I was a Black student, because it was an argument between me and some of the Palestinian kids, and she was also Palestinian, and one of the kids was her relative. They didn’t end up getting in trouble, and she tried to get me in trouble.

If there was like a substitute teacher, if there was a disruptive class, uh, I was always going to be the one that someone tried to make an example of.

I had a real quick mouth at a certain point when it came to things because I didn’t take to that very kindly. Uh, I had something, one substitute teacher saying something along the lines of, were you raised by animals or something? Which she had said, which was funny because she said it to me in response to laughing at a rude comment someone else had made. So, one of the Pakistani kids had said something very disrespectful to one of the other girls, like he told her she has the face of a pig. And then I laughed, which was wrong. I shouldn’t have laughed in that situation. And then she spins around on me and just starts yelling and goes in, which I could tell she’d had an issue with me since I’d first come in. —Idris

Every time I would read Qur’an or something I would be put down. During grade five, I was sent to the principal’s office every day because “I was not memorizing” even though I would come to class with the ayat memorized. —Harun

5. Lack of Respect for Students’ Identity, Culture, and History

Identity: Who is a Muslim?

“Where are you from? Where are your parents from? How can you be Muslim when you aren’t from a Muslim country?” The issue around resistance to accepting Black Americans’ Islam came up in every aspect of this mixed-methods study. Black students would be asked questions like the above.

I was often made to feel and often received negative comments on being Black and Muslim. Such as: “You are not a real Muslim because you aren’t Arab.” —Ayesha

Identity is a useful tool to understand these questions. The teachings of Islam stipulate one community, based on faith in God, a community “raised up to encourage what is good and denounce evil.” It is a community committed to Prophetic ethics, including mercy, justice, and building institutions upon this basis. If this is what defines the Muslim community, then it should not matter when you joined the ummah (Muslim community), what language you speak, the color of your skin, your gender, or socioeconomic background.

All these things are part of who we are, but they do not define us. Even our actions do not define us. God defines the Muslim communities in the following three verses in the Qur’an: submissive servants to God (2:128), upright witnesses over humanity (2:143), and people who enjoin what is right and forbid what is wrong (3:110).

Bridging the gap between defining Muslims based on cultural norms (Muhammad 2010) and using the definitions given by God in the scripture can be a step towards accepting and embracing Black Muslims in IMIL Islamic schools.

Having established the broadest definition of Muslims, we must acknowledge that different cultures exist. Some children and adults who have not been exposed to other iterations of the faith cannot honestly understand the various cultures that make up the Muslim American landscape. Islamic schools can play a role in educating staff and students to recognize that Black Muslim Americans come from a variety of cultures: West African, East African, the Caribbean, African American, and a combination of these backgrounds and more.

Imaad recalls being asked “Where are you from?” and responding “Maryland.” He was then asked, “Where are your parents from?” “Maryland and Jamaica.” Then they were confused, are you really a Muslim?

Nzingha shared her story of entering an immigrant Islamic school and her identity being questioned:

My first experience of Islamic school was preschool through third grade. I’m African American. My parents are converts. I went to Sister Clara Muhammad school here in Chicago area. So my environment at the time was all Black. Everybody looked like me. So my sense of belonging was just, this is what the world is like, because that’s all I ever knew.

So that was the world as I knew it. Then because that school closed down, I was in public school for a couple of years. That did an absolute number on my Islam for sure. Um, so my parents learned about this Islamic school way out in the suburbs. Um, that is majority Palestinian and was about an hour away from where we lived… So this school was out in what would be, like, a blue collar, uh, neighborhood, um, which that came with its own, like, sense of trauma because I, you know, I was very well educated and steeped in understanding of Black history and where we came from, so being out there in, quote unquote, redneck territory was its own, kind of, um, that came with its own anxieties and things like that, but then being kind of put in this school where I had never met, I had never met Arabs. My entire Muslim world was Black Muslims. We had one teacher in my school who was from Pakistan. She was our, I think she was the Islamic studies teacher, but that was it for like my cultural awareness of other Muslims. I very quickly started getting a lot of, “Oh, well, you can’t be Muslim if you guys don’t speak Arabic.” “If you guys don’t speak Arabic at home, you’re not Muslim.” Or, “You can’t be Muslim if your mom wears her scarf differently than we do it.”

“That’s not Islam. You guys aren’t Muslim.” So there was a lot of that, um, that happened. That experience being very different from my childhood experience really accounts for my feeling of not belonging, um, in my second set of schools from my first.

Salma also shares that she was told, “You can’t be Muslim if you don’t speak Arabic.”

The Arabs were at the top of the hierarchy and the Blacks were at the bottom. And that hierarchy was perpetuated. —Noor

While 39% of survey participants felt that their practice of Islam was not seen as “valid” by their peers, Jamilah shared that “my practice of Islam was ‘valid’ because I erased my Black identity and practiced the way everyone else did.” Latifah, another survey participant, had a similar response: “Mine was seen as valid because, after all the years of attending, my practice mirrored that of my schoolmates. However, I sometimes got comments about the way my mother chose to wear her hijab (turban-style with neck uncovered)—even from people who didn’t wear hijab at all.”

Jalayla and Maimuna also raised this point when discussing the policing of clothing and the irony that your Islam as a Black woman was doubted because of hijab (head covering) while that same person wouldn’t do that to someone of their cultural background if they presented without hijab.

Black, Growing Up Arab, Growing Up Palestinian and School Connection

Latifah found a way to “fit in”, which led to a sense of connection to her teachers that remains until today. Of the 64 survey participants, 8 felt extremely connected to their teachers. Four attended BMBL Islamic schools, three attended The Islamic School of Seattle and the eighth was Latifah, who attended a IMIL school. Latifah scored her school quite high across the survey. No other participant from an IMIL school scored their school that high. I asked Latifah about this. She said, “I started school at three and graduated at eighteen; those were my formative years in life.” Latifah had two big sisters who did experience a difficult time at Unity, but Latifa was welcomed. Latifah continued, “I grew up Arab, I grew up Palestinian, I could fake it really well.” Latifa shared in the survey that she heard the word ‘abid used, but never directed at her. Latifah didn’t put her sons in Unity, as she didn’t want them growing up thinking they had to be Arab to be accepted. Latifah has fond memories and still sees some of her old teachers in the community.

Not good enough

A lack of acceptance of Black Muslims as part of a legitimate Muslim culture was a salient point mentioned often in this study. Jalaylah is 28 and shared the following:

I grew up in the community of Imam W. D. Muhammad. That informed my education, my practice of Islam, my style, like everything. And I think being in non-Black, Muslim educational environments, it slowly started to teach me that my community wasn’t considered good enough.

I remember at one point, kind of in my adolescent period, kind of like, feeling a sense of embarrassment from being a part of the community.

No one overtly said negative things to Jalaylah, but it was the pregnant silence when she would mention the name of her community in conversation or people having blank looks or acting as if it was made up.

It was assumed that my worship or practicing of Islam was not equal but less in quality because I was Black and not born into an Arab Muslim culture. —Asiya

Lack of Respect for Culture

Many participants said that they did not feel respected personally, in their practice of Islam, or in their cultural background by the teachers and their fellow students.

Rahmah succinctly shared, “Well, they didn’t really know there was a culture to respect.”

This sentiment was shared many times during the focus group. Their experience of invisibility of self and culture is evident in the numbers.

- 73% either felt no respect at all, a little respect, or some respect from their peers

- 70% either felt no respect at all, a little respect, or some respect from their teachers

- 81% either felt no respect at all, a little respect, or some respect for their culture from fellow students

- 77% either felt no respect at all, a little respect, or some respect for their culture from their teachers

Despite this, most students performed well academically and went on to successful careers. Many, however, carried a sense of “not fitting into” the Muslim community and at times not being “Muslim enough” for some spaces.

Many participants said having other older siblings or older Black children in the school helped them with dealing with unbelonging. Others said a strong Muslim identity at home and a strong knowledge that Black Muslims are Muslims and have been from the very beginning helped them navigate non-affirming environments.

What Makes Up the Ummah?

In theory, all Muslims are part of the global ummah. Yet in practice, some places are “more Muslim” or “less Muslim” than others. This identity politics is imported into the US and plays out in our schools across the nation. It is illustrated in a story Salma shared. Somalia was experiencing a drought when Salma asked her teacher if the class could pray for Somalia. “Millions are dying right now.” Salma shared with her class. To this, her teacher responded, “I heard you had lived in Somalia, but, you know, keep Palestine in your prayers because it’s a Muslim country.”

Salma was shocked because Somalia was a Muslim country also. “People are dying, couldn’t they just make dua (prayer) and leave it at that?” Salma clarified that she loves Palestine too, but she couldn’t understand why her teacher wouldn’t acknowledge the suffering of anyone else.

As a child, she concluded that “the only countries that matter in the Muslim world are Arab countries.” We see the same thing today where Muslims will engage in raising awareness about Palestine because it is a “Muslim land” but neglect Sudan and other parts of the Muslim world.

Significance of the Participant Demographics

As mentioned in my methodology, this study, unlike previous studies, is not limited to African Americans, or to Somali Americans. I invited alumni who present as Black and consider themselves Black to participate.

Below is the breakdown of how participants reported themselves:

- 7 reported as biracial

- 5 reported as East African

- 5 reported as West African

- 47 reported as African American

Black bodies are exposed to antiblackness regardless of cultural backgrounds and histories.

Culture and history do matter as Black Muslims are not a monolith. However, antiblackness knows no boundaries; thus, this study included all Black-identifying and -presenting alumni.

The next installment looks at the implications of this study for Muslim education leaders and our community as a whole.

[1] These include the Black run schools (except for one school that I will discuss later) and the Islamic School of Seattle, which was called ‘a groundbreaking school’ by Mariah, the daughter of one of the founders and a student there in the 80s. She also explained that “it was one of the first schools in the US.” Faiza, another alumni, survey respondent, and daughter of one of the group of founders shared that ‘the school was founded by a number of women from various racial backgrounds who came together with the intention of creating a nurturing space.’

[2] In the past few months, two schools reached out to me about the use of the n-word in their school. They didn’t know what to do, what disciplinary practices to enforce or policies to put in place, or how to cultivate a climate where students did not use this language. Neither Midwest school followed up with me after admitting to their problem.

[3] I was surprised that an accredited school would not be teaching any African History, so I asked. I was told that they studied a couple of chapters about Egypt. “And then they mentioned the slave trade happened in West Africa and that was bad and we’re sorry about that. And that’s about it.”

Here are links to the other installments in this series: Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5

Rukayat Yakub is the author of the 2023 Black Belonging Study and serves as an instructor at Ribaat Academic Institute. She received her teaching certification in Montessori elementary education and earned her Master of Arts in Islamic Education. She is working on a Doctorate in Ministry to further her studies in belonging and community development.

An award-winning children’s author, educator, publisher, trainer, consultant, and school culture coach, Rukayat has worked in education for 25 years. Her expertise includes Heartwork (addressing anti-blackness to build spaces of prophetic belonging), integrated curriculum design, History, and ethical wealth flow. She works with leaders to develop and implement best practices that infuse prophetic courage, kindness, and humility in community institutions. Her websites are rukayatyakub.com and www.lightlegacybooks.com

She can be reached at rukayaty@gmail.com